E4 - Traumatic Memories

In the episode we’re going to talk about what a traumatic memory is, how it’s stored in the brain, and how it may be remembered differently in comparison to other memories in our life. As we’ve discussed in previous episodes, trauma has a both a biological and psycho-social impact. I’m going to quickly recap these changes.

Biological impact

Intense psychological stress caused by unwanted, troublesome memories can cause brain structures such as the amygdala, hippocampus and frontal cortex to become activated, as they process the memory. The fMRI machine we talked about in episode 3 showed that those who are susceptible to PTSD actually have a hippocampus with a reduced size. Research has also demonstrated the adrenal activity from intense stress dramatically increases activity in the amygdala and leads to changes in brain functioning as well as altering physiological indicators of stress; heart rate and blood pressure.

Children who have been exposed to traumatic events often display hippocampus-based learning and memory deficits. These children suffer academically and socially due to symptoms like fragmentation of memory, intrusive thoughts, dissociation and flashbacks, all of which may be related to hippocampal dysfunction.

Psycho-social impact

People who are feeling distressed by unwanted traumatic memories, which they may constantly be "reliving" through nightmares or flashbacks may withdraw from family or their social circles in order to avoid exposing themselves to reminders of their traumatic memories. Physical aggression, conflicts and moodiness cause dysfunction in relationships with families, spouse, children and significant others. In order to cope with their memories they often resort to substance abuse, drugs or alcohol in order to deal with anxiety. Depression and severe anxiety disorders commonly stem from traumatic memories.

How does your memory work?

As Emily Dickinson once said, "the mind is wider than the sky," and this is very true when it comes to the complexity of storing memories. The cerebrum, or forebrain, makes up the largest part of the brain, and it is covered by a sheet of neural tissue known as the cerebral cortex, which envelops the part of our brain where memories are stored.

Items in short-term memory, such as a telephone number remembered for a few moments, will often be forgotten by the brain unless there is constant repetition. Long-term memory is typically involved in retaining information for lengthier periods of time, like remembering the birth of your child. There is increasing debate over whether we actually forget something, or if it just becomes more difficult to remember.

How long-term memory functions has multiple answers dependent upon different types of memories and different ways they work. Procedural memory, the unconscious memory of skills, for example, knowing how to ride a bike, is dependent upon repetition and practice and will operate automatically like muscle memory. Declarative memory, 'knowing what,' is memory of facts, experiences and events.

Although your brain does typically automatically store your experiences into a form of memory, there are times where your brain "walls off" a memory of a traumatic experience -- for its own good. We’ll dive into that a little deeper later on in this episode.

Ok so now let’s talk about what consolidation and reconsolidation of a memory is.

Consolidation

Memory Consolidation is the processes of stabilizing a memory trace after the initial acquisition. It may perhaps be thought of part of the process of encoding or storage of the memory. It consists of two specific processes, synaptic consolidation (which occurs within the first few hours after learning or encoding) and system consolidation (where hippocampus-dependent memories become independent of the hippocampus over a period of weeks to years).

Neurologically, the process of consolidation utilizes a phenomenon called long-term potentiation, which allows a synapse to increase in strength as increasing numbers of signals are transmitted between the two neurons. Potentiation is the process by which synchronous firing of neurons makes those neurons more inclined to fire together in the future. Long-term potentiation occurs when the same group of neurons fire together so often that they become permanently sensitized to each other. As new experiences accumulate, the brain creates more and more connections and pathways, and may “re-wire” itself by re-routing connections and re-arranging its organization.

As we know, traumatic memories are formed after an experience that causes high levels of emotional arousal and the activation of stress hormones. These memories become consolidated, stable, and enduring long-term memories (LTMs) through the synthesis of proteins only a few hours after the initial experience. The release of the neurotransmitter Norepinephrine, also known as Noradrenaline, plays a large role in consolidation of traumatic memory. Stimulation of beta-adrenergic receptors during arousal and stress strengthens memory consolidation. Increased release of Norepinephrine inhibits the prefrontal cortex, which plays a role in emotion control as well as extinction or suppression of memory. Additionally, the release also serves to stimulate the amygdala which plays a key role in generating fear behaviors.

Reconsolidation

Memory reconsolidation is a process of retrieving and altering a pre-existing long-term memory. Reconsolidation after retrieval can be used to strengthen existing memories and update or integrate new information. This allows a memory to be dynamic and plastic in nature. Just like in consolidation of memory, reconsolidation, involves the synthesis of proteins. When a memory is reactivated it goes into a labile state, making it possible to treat patients with post-traumatic stress disorder or other similar anxiety based disorders. (This is good news yay!) This is done by reactivating a memory so that it causes the process of reconsolidation to begin. One source described the process this way: "Old information is called to mind, modified with the help of drugs or behavioral interventions, and then re-stored with new information incorporated."

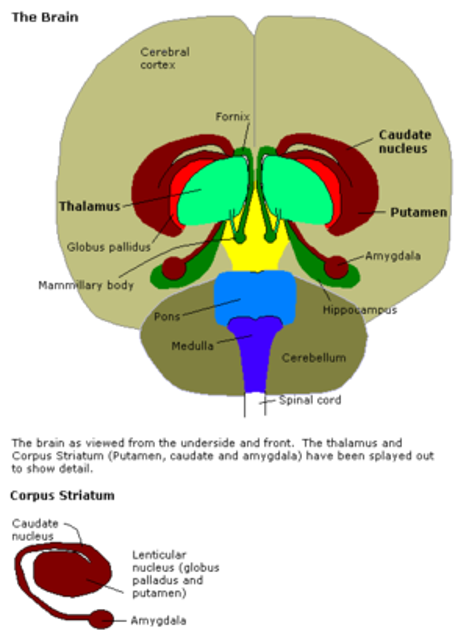

On my blog, you can find notes on all of my episodes if you’d like to review the information again. I also sometimes include helpful diagrams and images. I’m about to describe the importance of the amygdala and there’s an image of the brain that may be helpful on my blog for this episode. My blog can be found at foxinejay.com/traumamama

The importance of the amygdala

Amygdalae are shown in dark red. The amygdala is an important brain structure when it comes to learning fearful responses, in other words, it influences how people remember traumatic things. An increase in blood flow to this area has been shown when people look at scary faces, or remember traumatic events. Research has also shown that the lateral nucleus of the amygdala is a crucial site of neural changes that occur during fear conditioning. Some stressful experiences — such as chronic childhood abuse — are so overwhelming and traumatic, the memories hide like a shadow in the brain.

At first, hidden memories that can’t be consciously accessed may protect the individual from the emotional pain of recalling the event. But eventually those suppressed memories can cause debilitating psychological problems, such as anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder or dissociative disorders.

A process known as state-dependent learning is believed to contribute to the formation of memories that are inaccessible to normal consciousness. Thus, memories formed in a particular mood, arousal or drug-induced state can best be retrieved when the brain is back in that state. Studies have shown that best way to access the memories in this system is to return the brain to the same state of consciousness as when the memory was encoded.

That’s why some trauma therapy (like DBT, dialectic behavioral therapy) does something called imaginal exposure. How this work is first, you write a hierarchy of traumatic memories. Then you take each memory one by one with your therapist and record a 20 min retelling of that memory. As best as you can, from the first person present. You put yourself back there and tell the storyline of the memory as if it’s happening to you then and there. If the story doesn’t last a full 20 mins, you retell it over and over until 20 mins has passed. Once you’ve completed the retelling, you go home and for a week you listen to that memory once a day and record your emotional reaction to it. It’s an incredibly painful and grueling process. I did this with about 6 memories and afterwards I was wondering why I wasn’t as upset about each one as I used to be. That’s the whole point. That’s called growth!

Brain Chemistry of a Traumatic Memory

The brain develops from the bottom up and the inside out. The lowest brain centers hold our most primitive survival reactions and the upper brain centers serve a regulating and reflective purpose.

The lowest brain centers, sometimes referred to as the reptilian brain, are involved with activating defensive stress reactions. These centers reflexively respond to fearful events and stimuli with a startled response, increased heart rate, quickened breath, and increased muscle tension.

The middle area of the brain is called the limbic system, which provides the neural basis for memories and emotions. Within the limbic system, the amygdala and hippocampus work in conjunction with each other for memory encoding and retrieval; however, they have very different roles. The amygdala is primarily responsible for the emotional content of memories. The amygdala acts as a warning system for the brain and body by scanning the environment for potential danger and relaying this information to the hypothalamus. The hypothalamus initiates a set of actions in the endocrine system to release hormones and engage the body’s stress related responses. Hormones and neurotransmitters initiate a cascade of responses leading to a whole-body experience of fear related sensations and emotions. (Fight, flight, freeze, fawn)

In contrast, the hippocampus is essential in long-term memory for facts. This brain structure helps the brain place specific memories within the context of thousands of other previous life experiences. This is the process of consolidation which we talked about earlier, and involves linking sensory components of a memory into the association cortex so that the sounds are held in the auditory context, scents in the olfactory cortex, and so forth.

The most recently evolved area of the brain is the neocortex and more specifically, a portion called the prefrontal cortex. This area allows us to be self-reflective about our emotional or somatic experience and inhibits unnecessary stress reactions.

Implicit and Explicit Memories

We have two types of memories, implicit and explicit. Implicit memories involve the lower regions of the brain, the reptilian and limbic brain centers, specifically the amygdala. These are sometimes referred to as body memories or nonverbal memories because they are stored as motor patterns and sensations. Examples of an implicit traumatic memory might include feeling suddenly nauseous, panicked, or frozen with or without a clear understanding as to why this is happening now. I have experienced this a lot when it comes to panic attacks and it’s frustrating. You’ll be having this intense physical reaction to a moment and not able to articulate why to someone when they ask what’s wrong or what’s going on.

Explicit memories are long-term memories that include our knowledge of basic facts and a sequence of events including time and place, where it happened, and who was there. Our explicit memories rely upon the process of consolidation that we just spoke about.

Pre-Cognitive and Post-Cognitive Circuits

The brain processes incoming sensory information in two ways: precognitive and post cognitive. In the precognitive circuit, lower brain centers respond to potential danger without engaging upper brain centers. Therefore, we react without consciously reflecting on the details of the situation. From an evolutionary perspective, this is important. If you were to meet a tiger in the wild, it would be wise to run quickly rather than take the time to think about it. Only after the threatening event would we pause and reflect upon the event. This is what we were talking about in episode 2 regarding the fight, flight, freeze, and fawn response.

The post cognitive circuit involves activation of the prefrontal cortex. This allows us to assess the situation while it is happening and consciously reflect on how we want to respond.

When people talk about memories, most of the time we refer to conscious or explicit memories. However, the brain is capable of encoding distinct memories in parallel for the same event — some of them explicit and some implicit or unconscious.

An experimental example of implicit memories is threat conditioning. In the lab, a harmful stimulus such as an electric shock, which triggers innate threat responses, is paired with a neutral stimulus, such as an image, sound or smell. The brain forms a strong association between the neutral stimulus and the threat response. Now this image, sound or smell acquires the ability to initiate automatic unconscious threat reactions — in the absence of the electric shock.

It’s like Pavlov’s dogs salivating when they hear the dinner bell, but these conditioned threat responses are typically formed after a single pairing between the actual threatening or harmful stimulus and a neutral stimulus, and last for life. Not surprisingly, they support survival. For example, after getting burned on a hot stove, a child will likely steer clear of the stove in order to avoid the harmful heat and pain.

Studies show that the amygdala is critical for encoding and storing associations between a harmful and neutral stimuli, and that stress hormones and mediators — such as cortisol and norepinephrine — play an important role in the formation of threat associations.

Researchers believe traumatic memories are a kind of conditioned threat response. For the survivor of a bike accident, the sight of a fast approaching truck resembling the one that crashed into them may cause the heart to race and skin to sweat. For the survivor of a sexual assault, the sight of the perpetrator or someone who looks similar may cause trembling, a feeling of hopelessness and an urge to hide, run away or fight. These responses are initiated regardless of whether they come with conscious recollections of trauma.

Conscious memories of trauma are encoded by various sites in the brain which process different aspects of experience. Explicit memories of trauma reflect the terror of the original experience and may be less organized than memories acquired under less stressful conditions. Typically traumatic memories are more vivid, more intense and more persistent.

Traumatic Memory

Now, we can turn our attention to the subject of traumatic memory to better understand why details may be unclear or forgotten:

In situations of physical or sexual abuse there is a high level of threat. Therefore, the precognitive circuit is activated reducing the likelihood that we are engaging the prefrontal cortex. Meaning, we are having an unconscious reaction verses a thought-out response.

Being highly aroused emotionally actually disrupts the functioning of the hippocampus, impairing our ability to recall all the details or maintain a sense of sequential timing of events. We might have only fragments of sensory details.

During traumatic events, bursts of adrenaline activate the amygdala leading isolated sensory fragments to be vividly recalled. Specific sensory details such as visual images, smells, sounds, or felt experiences can be strongly imprinted and recalled.

Broca’s area, which is located in the frontal lobe and supports our language capacities, is also impacted by traumatic stress. Thus, it becomes significantly harder to verbalize about experiences both immediately following the event and later when trying to describe the event to others.

In situations where abuse is ongoing, the functioning of the prefrontal cortex may be altered by ongoing exposure to stress hormones. This impairs the capacity to reflect upon or regulate our emotional states. This is something we talked about in our last episode, episode 3 when we discussed emotional dysregulation.

How does your brain cope with trauma?

If the brain registers an overwhelming trauma, then it can essentially block that memory in a process called dissociation -- or detachment from reality. The brain will attempt to protect itself. Dissociation causes a lack of connection in a person's thoughts, memory and/or sense of identity. The same way the body can wall-off an abscess or foreign substance to protect the rest of the body, the brain can dissociate from an experience. In the midst of trauma, the brain may wander off and work to avoid the memory. However, not all psyches are alike, and what may be severe trauma for one person may not be as severe for another person.

A person's genetic makeup and their environment can both contribute to how the trauma is received. There is still a great debate in the scientific community between nature and nurture -- the argument that determines if a person's development is predisposed in their DNA, or if it is influenced mainly by environment -- and it can be assumed that both play a role.

These severe types of dissociation are frequently seen with someone who experiences significant trauma, and may not happen to everyone who experiences the same trauma. Dissociation can happen as a part of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), but these conditions can also be independent of each other.

Repressed Memories

The term Repressed memories refers to the rare psychological phenomenon in which memories of traumatic events may be stored in the unconscious mind and blocked from normal conscious recall.[1] As originally postulated by Sigmund Freud, repressed memory theory claims that although an individual may be unable to recall the memory, it may still affect the individual through subconscious influences on behavior and emotional responding.[2]

Repressed memories have been reportedly recovered through psychotherapy (or may be recovered spontaneously, years or even decades after the event, when the repressed memory is triggered by a particular smell, taste, or other identifier related to the lost memory). According to the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, it is possible for adults to not remember episodes of childhood abuse, even in circumstances where there are definitive records that abuse occurred. However, the American Psychological Association also warns about the possibility of constructing "pseudo-memories" through problematic recovered-memory therapy sessions.

Mechanisms of a repressed memory

There are three mechanisms of normal memory processing that may explain how memory repression may occur: retrieval inhibition, motivated forgetting, and state-dependent remembering.

Retrieval inhibition

Retrieval inhibition refers to a memory phenomenon where remembering some information causes forgetting of other information.[48] Anderson and Green have argued that for a linkage between this phenomenon and memory repression; according to this view, the simple decision to not think about a traumatic event, coupled with active remembering of other related experiences (or less traumatic elements of the traumatic experience) may make memories for the traumatic experience itself less accessible to conscious awareness.

Motivated Forgetting

This phenomenon, which is also sometimes referred to as intentional or directed forgetting, refers to forgetting which is initiated by a conscious goal to forget particular information. In the classic intentional forgetting paradigm, participants are shown a list of words, but are instructed to remember certain words while forgetting others. Later, when tested on their memory for all of the words, recall and recognition is typically worse for the deliberately forgotten words.

State dependent remembering

The term state-dependent remembering refers to the evidence that memory retrieval is most efficient when an individual is in the same state of consciousness as they were when the memory was formed.